Field

Social Sciences

Subfield

Health

Impact of Men’s Labour Migration on Non-migrating Spouses’ Health: A Systematic Review

Shraddha Manandhar1, Padam Simkhada1, Philip Brown1

, Edwin van Teijlingen2

Affiliations

Abstract

International migration is in an increasing trend globally; internal migration is also very common, particularly in low- and middle- income countries (LMICs). Little attention has been paid to the impact of men’s migration on non-migrating women’s health. Therefore, we undertook a systematic review to examine the impact of men's migration on the health of women who remain behind in LMICs. We searched five databases, CINAHL, Google Scholar, PsychINFO, PubMed and Scopus, for publications from 2005 to 2022 using key search terms 'left-behind', 'women' and 'migration'. Thirty-three peer-reviewed publications were included in the review. Findings suggest that left-behind women had increased access to healthcare due to better financial positions (via remittances) and experienced more empowerment/autonomy in the absence of their husbands. This resulted in increased (a) decision-making regarding their health and (b) freedom of mobility to seek healthcare. Remittances led to improved food and housing security, a critical wider determinant of health. However, some studies reported that in the longer term, the physical health of women who remain behind was negatively impacted. Almost all studies on mental health reported higher depressive symptoms among migrant wives compared to women co-habiting with their spouses. Left-behind women feared contracting sexually transmitted infections from their migrant partners. National and local policies should include support groups and counselling services at the local health centre for women who remain behind. We recommend further studies on the areas presented above as well as unexplored areas such as vulnerability to violence and impact of remittance on health and nutrition.

1. Introduction

Migration is a widespread global phenomenon engaging an estimated 281 million international migrants in 2020 which is roughly 3.6% of the global population (McAuliffe & Triandafyllidou, 2021). The extent and diversity of international migration is increasing worldwide and is expected to escalate further with expanded connectivity, population growth, inequalities, climate change and demographic imbalances (IOM, 2019). Nearly 8 in 10 international migrants were of working age (15-64 years), and over half are men (McAuliffe & Triandafyllidou, 2021); two-thirds are labour migrants (IOM, 2020). The reasons why people migrate include demand for labour, instability in the country of origin, economic crisis, conflict, economic development and unemployment in host country, communications technology advances and increased ease of transport globally (IOM, 2020). The most common migration pattern or ‘migration corridor’ is that from low- and middle- income countries (LMICs) to high-income countries (HICs) (McAuliffe & Triandafyllidou, 2021). Migration within countries, or internal migration, from rural or sub-urban areas to developed cities for employment or education is also common with an estimated 740 million internal migrants globally in 2009 (UNDP, 2009).

In LMICs, labour migration, particularly international migration, typically means one of the spouses, most commonly men, migrates to earn a living, while the other spouse, commonly the women, remains at home to take care of their family. Such migration can result in long periods (often years) of separation within the family/household (Lokshin & Glinskaya, 2009). Therefore, it is important to understand how men’s labour migration impacts the health and wellbeing of left-behind women. Whilst prolonged separation from spouses has numerous implications for the women who remain behind, there is a lack of consensus about the form these impacts take (Fakir & Abedin, 2020). Physical and mental stress due to increased responsibilities, and loss of physical and emotional intimacy is likely to adversely affect their health. Several wider factors may additionally affect the women’s health including whether enough remittances are being sent, whether they are living in a nuclear, joint or extended family, their relationship with their spouses and the migrants’ living and working conditions abroad.

While research on migration has been increasing over the past two decades, most studies focus on migrant men (Fernández-Sánchez et al., 2020; Nawyn, 2010), and are based on receiving countries or HICs (IOM, 2020). In terms of migration issues studied, the focus has been on how migrants make economic, social and political contributions for both sending and receiving countries, the conditions in which migrants live in destination countries and how this can be improved (IOM, 2020). However, migration studies based on LMICs or sending countries, and those based on the family members ‘left-behind’ remain scarce (IOM, 2020). While migration research focusing on the experience of and impacts of women has been growing steadily since the 1970s (Boyd & Grieco, 2003; Hondagneu-Sotelo, 2000), the balance tends to be towards women as migrants (Nawyn, 2010). Feminist migration scholars have argued that it is important to study women left-behind, including what prevents women from migrating, how their position changes or not when their partners migrate (Boyd & Grieco, 2003; Hondagneu-Sotelo, 2000; Toyota et al., 2007). To date studies on women who remain behind focus more on their role in collective decision-making regarding migration, and less on the consequences of migration (Toyota et al., 2007). By focusing on the women left-behind, their voices and experiences, which form a critical part of the migration experience, can be understood (Toyota et al., 2007).

Migration health research too has focused disproportionately on migrants only. Diverse areas including the threats to migrant health in terms of working conditions, migrants' access to health services and screening of migrants for communicable diseases such as tuberculosis have been studied, and various categories of migrants including labour migrants, students and refugees have been studied (Zimmerman et al., 2011). Migration and health studies have again overlooked the left-behind family members, particularly left-behind spouses (Zimmerman et al., 2011). Therefore, we conducted this review to analyse what is known about the impact of men’s migration on the health of women who remain behind and explore gaps in the knowledge base. This work is both timely and original as by exploring the health impacts of migration and the resultant separation on women who remain behind will allow us to understand how migration is played out in a more holistic way and will contribute new insights in the gendered experience of migration and health.

2. Methods

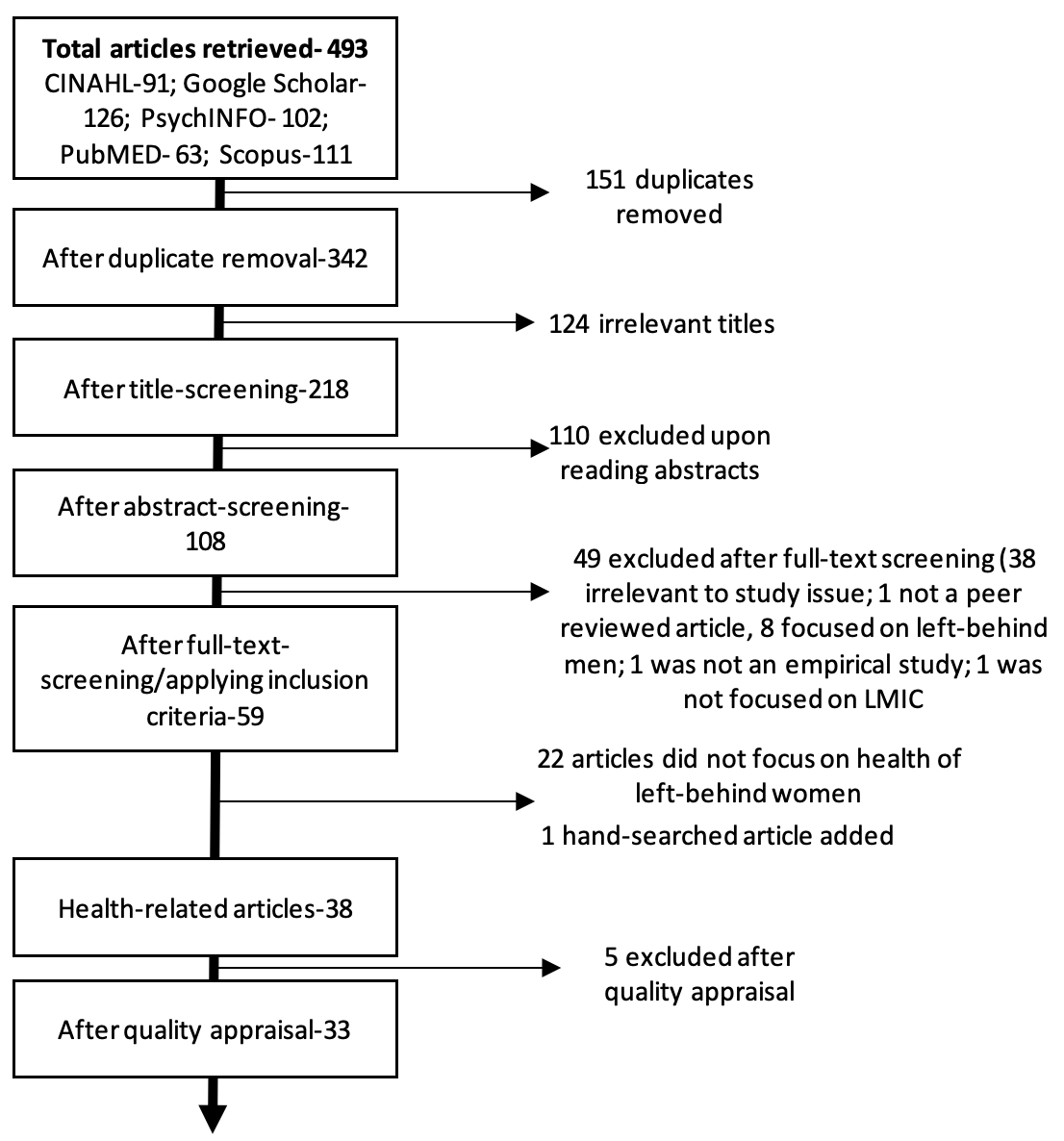

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist (Moher et al., 2009) was used as a guideline in this review (Figure 1):

2.1. Database search

Using key search terms 'migration', 'left-behind' and 'wives/partners/ women/spouses', we retrieved 493 articles published between 2005 and September 2022 from five databases: CINAHL, Google Scholar, PsychINFO, PubMED, and Scopus.

2.2. Article screening and selection

Initially, 493 searches were retrieved from the five databases and narrowed down to 59 articles post duplicate removal, title, abstract and full-text screening. The inclusion criteria were: focus on left-behind wives (women who remained behind) of migrant (internal and international) men; peer-reviewed publication; focus on LMICs; empirical studies (qualitative, quantitative or mixed-methods); published between 2005 and September 2022; and articles published in English language only.

Out of the 59 articles, 37 were related to health impacts. One additional article identified via hand-searching was included resulting in a total of 38 health-related articles. While there have been published reviews on general impacts of migration on the left-behind women, there were no specific reviews on health impacts. Therefore, we made the decision to focus only on health impacts on left-behind women in this manuscript.

2.3. Quality assessment

The quality of the 38 articles was appraised using the JBI tool for quantitative articles (Moola et al., 2020), CASP checklist for qualitative articles (CASP, 2018), and MMAT tool for mixed methods studies (Hong et al., 2018). Five studies were excluded on quality grounds leading to a total of 33 studies being included in this review.

2.4. Data extraction and synthesis

From the 33 selected articles, relevant information including study title, author (s), year of publication, study type and summary of findings were extracted in a data extraction tool hosted within an Excel spreadsheet. A summary of the extracted data from all studies is presented in Table 1. Due to the diverse nature of the selected studies in terms of the methods employed, a narrative analysis (Popay et al., 2006) was conducted wherein major themes were developed inductively from extracted data. The extracted data were fed onto NVIVO software, coded and analysed.

3. Findings

Out of the 33 studies, 28 were from Asia alone (16 from South Asia and 12 from rest of Asia), four were from Africa and one from the Caribbean. Twenty-four were quantitative in nature, four were qualitative and five mixed methods. Fifteen studies explored mental health, 13 looked at sexual and reproductive health, ten at physical health, five at health-care accessibility and four studies focused on other health related issues. The analytical themes have been categorized based on health outcomes and discussed below:

3.1. Mental health

Of the fifteen studies focusing on mental health, thirteen were conducted in Asia, one in Africa and one in the Caribbean. Nine studies argued that left-behind women had a higher risk of mental ill-health compared to women who lived with their spouses (Bhurtyal & Wasti, 2021; Gartaula et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2018; Jin et al., 2016; Lu, 2012; Nikoloski et al., 2019; Siriwardhana et al., 2015; Tong et al., 2019; Yi et al., 2014). Prevalence of depression/depressive symptoms was higher among left-behind women compared to women co-habiting with spouses (Bhurtyal & Wasti, 2021; Jin et al., 2016; Lu, 2012; Nikoloski et al., 2019; Tong et al., 2019; Yi et al., 2014). Another cross-sectional study in Sri Lanka found that common mental disorders (depression, somatoform disorders and anxiety) were higher among spouses of migrants compared to the national average (Siriwardhana et al., 2015). However, a cross-sectional study in Iran found no difference in depression among migrant and non-migrant wives. They hypothesized that this may be because of the deep-rooted Iranian tradition of men migrating leading to women being accustomed to their absence (Aghajanian et al., 2014). Only one cross-sectional study conducted in Nepal showed a lower than the national average mental ill-health risk among left-behind women with 6% reporting mild or moderate depression (Aryal et al., 2020). Findings from their study showed that frequent communication with husbands and high frequency of remittance was associated with a lower mental ill-health risk and high resilience among left-behind women (Aryal et al., 2020).

The factors negatively affecting mental health among left-behind women included marriage/relationship, family, finances and other factors. Marriage/relationship related factors included: loneliness due to absent spouse (Arokkiaraj et al., 2021; Gartaula et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2018; Malik & Aftab, 2015; Thapa et al., 2019; Tong et al., 2019; Wrigley-Asante & Agandin, 2015); longer duration of separation (Lu, 2012; Siriwardhana et al., 2015; Tong et al., 2019); insecure marriage (Arokkiaraj et al., 2021; Malik & Aftab, 2015; Wrigley-Asante & Agandin, 2015; Yi et al., 2014); less communication with husbands (Arokkiaraj et al., 2021) and uncertainty regarding the future (Wrigley-Asante & Agandin, 2015). Malik and Aftab’s qualitative study in Pakistan found that women worried about the condition of their husbands abroad and reported feeling insecure and unsafe in their homes in the absence of a man (Malik & Aftab, 2015). Family related factors negatively affecting the mental health included: living in a nuclear family as de-facto household head (Gartaula et al., 2012); disrespectful behaviour from in-laws/relatives (Arokkiaraj et al., 2021); having suffered from domestic violence (Jin et al., 2016), including sexual violence (Wrigley-Asante & Agandin, 2015); and having an illiterate (and therefore more likely to be conservative) household head (Bhurtyal & Wasti, 2021). Finance-related factors include: low remittance/income (Arokkiaraj et al., 2021; Siriwardhana et al., 2015; Yi et al., 2014); having debts (Arokkiaraj et al., 2021); and reduced agricultural output (Wrigley-Asante & Agandin, 2015). Other factors negatively affecting the mental health of migrant wives were: increased workload due to childcare, agriculture and other household responsibilities (Arokkiaraj et al., 2021; Gartaula et al., 2012; Malik & Aftab, 2015; Siriwardhana et al., 2015; Tong et al., 2019; Wrigley-Asante & Agandin, 2015); older age (Arokkiaraj et al., 2021; Aryal et al., 2020; Jin et al., 2016); and passive coping styles (handling emotions rather than problems leading to emotions) (Malik & Aftab, 2015; Yi et al., 2014)]. A qualitative study in Pakistan, however, found that younger women reported feeling lonelier and missing their husbands. Their study also found that left-behind women coped with missing their husbands by keeping themselves busy in daily chores, by reminding themselves that their husbands migrated for the family’s good, and by communicating with family and community networks (Malik & Aftab, 2015). Huang et al. in their cross-sectional study elaborated that women who experienced prolonged stress and loneliness, may be hesitant to communicate and form effective social relationships (Huang et al., 2018).

Whereas the protective factors for mental health among left-behind women included: frequent communication with spouse (Aryal et al., 2020; Malik & Aftab, 2015); family/social support (Arokkiaraj et al., 2021; Gartaula et al., 2012; Lu, 2012); having children (Bhurtyal & Wasti, 2021); higher remittance/income/standard of living (Arokkiaraj et al., 2021; Jin et al., 2016; Siriwardhana et al., 2015); having property in one’s name (Bhurtyal & Wasti, 2021) and being educated (Bhurtyal & Wasti, 2021).

| Citation | Study setting | Study design | Study population | Health-themes covered | Health related finding (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agadjanian et al., 2011 | Mozambique | Cross-sectional survey | 1,680 women (689 migrant wives and 991 non-migrant wives) aged 18-40 years | STI | Migrant wives more likely to report that husbands had other sexual partners; the odds of knowledge/suspicion of husband’s infidelity among wives of migrants were 45% higher than wives of non-migrants. Migrant wives were more likely to worry about getting infected by HIV/AIDS from migrant husbands compared to non-migrant wives. Wives of successful migrants were more likely to think that husbands would object to condom use. |

| Agadjanian & Markosyan, 2017 | Armenia | Cross-sectional survey | 1030 women (670 left-behind women and 360 non-left behind women) | STI | Migrant wives were more likely to suspect their husbands of infidelity and worry about contracting HIV than non-migrant wives. No difference in condom usage among migrant and non-migrant wives. |

| Aghajanian et al., 2014 | Iran | Cross-sectional survey | 402 married women of age 15-55 years | Mental health; physical health; STI | No significant differences in physical and mental health of migrant wives and wives of non-migrants. Wives of migrant men, particularly in urban areas, reported having a higher rate of STI symptoms. |

| Agadjanian et al., 2021 | Mozambique | Quantitative (panel) study | 1678 women (migrant and non-migrant wives) | Mortality | Women married to less successful migrants had higher mortality risks than women married to more successful migrants. |

| Ali et al., 2017 | India | Cross-sectional survey | 11,937 married women (1192 migrant & 10,745 non-migrant wives) | Physical health | Incidence of chronic and other diseases was higher among non-migrant wives compared to migrant wives. |

| Arokkiaraj et al., 2021 | India | Mixed methods | Interview (provided quantitative and qualitative data)- 132 left-behind women FGD-3 | Mental health | Factors associated with higher psychological problems for left-behind women: low family (in-laws) cohesion/support; low levels of shared responsibilities (social & financial) with in-laws; child-care; debt; receive remittances late; feel lonely/insecurity; less communication with husbands. |

| Aryal et al., 2020 | Nepal | Cross-sectional-survey | 382 left-behind women | Mental health | 3.1% left-behind women had mental-health risk; 6% moderate depression. Frequent communication with husband and receiving remittance regularly was associated to a lower mental ill-health risk / high resilience in left-behind women. |

| Bhurtyal & Wasti 2021 | Nepal | Cross-sectional-survey | 800 women (400 wives left behind and 400 wives of non-migrants) | Mental health | Left-behind wives were 11xs more likely to have depressive symptoms compared to wives of non-migrants. Factors associated with higher depression in left-behind wives include: low level education; no property in one’s one name, no children, being younger, illiterate household head. |

| Chen et al., 2015 | China | Secondary analysis of longitudinal dataset | 30,699 person-year records of 21–65-year-old individuals over a 15-year period (six waves of data) | Physical health | Married individuals who lived apart from spouses had clear physical health disadvantage compared to those living with their spouses. Individuals whose spouses were absent for a short-duration did not have a health disadvantage, those with spouses absent long-term, had worse health than those whose spouses were always present. |

| Gartaula et al., 2012 | Nepal | Mixed methods | Survey sample -277 households Qualitative case studies- 4 | Mental health; food security | Remittances increased well-being indicators, e.g., food, housing, health care, childcare. Women living with in-laws receive emotional support and help with household activities and childcare while disadvantages included lack of freedom, in some cases bad treatment from in-laws. Migrant wives felt lonely and missed husbands ‘all the time’. |

| Green et al., 2019 | India | Mixed methods | Surveys sample-689 left-behind women. In-depth interview-40 left-behind women | Health-care accessibility | Receiving regular/ frequent remittances, associated with. healthcare decision-making and freedom of movement to healthcare facilities These findings were corroborated by qualitative data as well. |

| Hendrickson et al., 2018 | Nepal | In-depth interviews | 20 left-behind women | Family planning | Women did not discuss family planning issues with husbands and delayed such conversations with their husbands until they returned. |

| Hendrickson et al., 2019 | Nepal | In-depth interviews | 20 left-behind women | Family planning | Women planned the use of temporary/permanent methods of family planning depending upon their husbands' visit or return. |

| Hendrickson & Underwood, 2020 | Nepal | Cross-sectional survey | 1793 married women aged 18–49 years | Family planning | Women with currently migrated or recently migrated spouses were less likely to have had spousal communication on family planning compared to women with husbands not recently or never migrated. |

| Huang et al., 2018 | China | Cross-sectional-survey | 3163 married women | Mental health; physical health | Being left-behind was negatively associated with physical health as well as psychological health. |

| Hughes et al., 2006 | South Africa | Cross-sectional survey | 208 migrant partners | STI | Over one-third feared contracting STIs from partners. Also feared communicating their concerns and only 8% used condoms (mainly to avoid pregnancy). Older women and women whose partner visited less regularly (1-4x p/a) more likely to fear contracting STI. |

| Jin et al., 2016 | China | Cross sectional survey | 938 women (439 left-behind & 499 non-left-behind women) | Mental Health | Most left-behind women had mild depression (40.7%) & 5.9% had moderate/severe depression. Left-behind was independent risk factor for depression among rural women. |

| Lei & Desai, 2021 | India | Panel survey (two waves of data, 2004/05 and 2011/12) | 19,737 women aged 15–49 years | Physical health | Husbands’ migration had negative effect on left-behind wives’ self-rated health. Factoring affecting self-rated health positively include better decision-making power, having cash to spend; factors affecting self-rated health negatively include eating separately from men, increased responsibility of animal care and holding a bank account. |

| Lu, 2012 | Indonesia | Secondary analysis of longitudinal dataset | 4391 adults aged 18-65 years | Mental health; physical health | Left-behind adults (including spouses) had 37% higher odds of hypertension controlling for smoking/overweight & double the odds of having depressive symptoms compared to non-migrant households. Hypertension risk/prevalence increased as the years went by, whereas depressive symptoms increased even in the first year of migration. |

| Malik & Aftab, 2015 | Pakistan | Qualitative | 10 married women from migrant households | Mental health | Women reported negative mental health experiences including sexual harassment, loneliness, anxiety, and lack of social support. |

| Nikoloski et al., 2019 | China | Secondary cross-sectional analysis | 14,332 adults aged 45 years or above | Mental health | Left-behind women had higher depressive symptoms than non-left behind women. |

| Nwankwo & Govia 2022 | Jamaica | Cross-sectional survey | 621 men and women of age 18 years and older | Mental health; physical health | Left behind women had higher odds of good physical health. |

| Sevoyan & Agadjanian, 2010 | Armenia | Cross-sectional survey | 1240 married women (migrant wives and non-migrant wives) aged 18-45 years | STI | Percentage diagnosed with at least one STI in past three years among migrant wives was almost 2.5x that non-migrant wives. Average number of reported STI symptoms higher among migrant wives. Among migrants whose income was low, STIs risks lower among migrant wives compared to non-migrant wives. Migrants with higher income, STI risks were significantly higher than in non-migrant wives. |

| Sevoyan & Agadjanian, 2015 | Armenia | Cross-sectional survey | 1238 married women (695 migrant wives and 543 non-migrant wives) | STI | Women married to migrants were more likely to talk to husbands about STIs compared those married to non-migrants, but much less likely to seek care for STI symptoms if they had not communicated to husbands regarding these symptoms compared to women married to non-migrants. |

| Shattuck et al., 2019 | Nepal | Cross-sectional survey | 1123 married women aged 15-24 years (485 migrant wives and 638 non-migrant wives) | Family planning; health-care accessibility | Women with migrant husbands had lower knowledge of fertility compared to women who live with husbands and were less likely to access reproductive health service/use contraceptives, but they had more autonomy and decision-making power re. seeking health care and when to get pregnant compared to women living with husbands.

|

| Shwe et al., 2020 | Myanmar | Cross-sectional survey | 205 migrant wives and 196 non-migrant wives of age 15-49 years | Health-care accessibility | Migrant wives’ decision-making (including health-related decision making) was significantly higher than non-migrant wives.

|

| Siriwardhana et al., 2015 | Sri Lanka | Cross-sectional survey | 465 respondents (277 migrant spouses and 188 non-spouse care givers) | Mental health | Common mental disorders (CMDs) (depression, anxiety, somatoform disorders) prevalence was higher among migrant spouses than national average. Spouses of migrant workers who had not returned were at higher risk of CMDs. |

| Sznajder et al., 2021 | Bangladesh | Mixed methods | Quantitative (panel) 621 married women interviewed in 2010 followed up in 2018 Qualitative sample- 48 left-behind women of age 20-65 | Physical health (nutritional status) | Migrant wives were less likely to be underweight but more likely to have a higher body fat % compared to wives of non-migrants. Most women thought labour migration was positive phenomenon with economic benefits. However, most expressed concerns related to chronic illnesses including, heart disease, blood pressure, strokes, diabetes and cancer. Ethnographic observations pointed to links between incomes, diets, and physical activity. |

| Thapa et al., 2019 | Nepal | Mixed methods | Survey- 9000 married women of reproductive age In-depth interviews: 15 migrants and their families left behind | Family planning; health-care accessibility; alcohol/smoking | High smoking and alcohol consumption among left-behind women. A significantly higher proportion of left-behind women went for antenatal check-ups compared to women living with husbands. Left-behind women also sought private care due to increased affordability. Left-behind wives decided with husbands to delay pregnancies & reported difficulties in conceiving after return of husbands. |

| Tong et al., 2019 | China | Secondary analysis of longitudinal dataset | 8708, 6346 and 5242 married adults of 20-54 years in 2010, 2012 and 2014 respectively | Mental health | Married adults with long-term migrant spouses had higher level of depressive symptoms. |

| West et al., 2021 | Bangladesh | Quantitative panel study

| 3,187 currently married women age of 15-45 in 1996 and followed up in 2012 | Health-care accessibility | Mobility restrictions including permission to get care was higher among migrant wives. No difference in reported physical health or lacking in necessary health care among migrant and non-migrant wives. |

| Wrigley-Asante & Agandin, 2015 | Ghana | Qualitative | 59 left-behind women

| Mental health | Left-behind women reported psychological strain for various reasons: burden of childcare; farming burden, worry that farming outputs will be insufficient; feelings of loneliness, insecurity and uncertainty; attitude in-laws; societal perception of migrants’ wives’ fidelity. |

| Yi et al., 2014 | China | Cross-sectional-survey | 1893 left-behind wives and 969 non-left-behind wives | Mental health; physical health | Status of being left-behind was an independent predictor of physical as well as mental health status. Left-behind wives have poorer health-related quality of life compared to non-left-behind wives. |

(NB: While most studies focused on left-behind women only, some focused on both left-behind men and women and therefore have been referred to as left-behind spouses in this table)

3.2. Physical health

Ten studies looked at the impact on physical health of left-behind women, out of which nine were conducted in Asia and one in the Caribbean. It is inconclusive whether being migrant wives affects their overall physical health negatively or positively.

Among the ten included studies, five reported negative impacts on physical health (Chen et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2018; Lei & Desai, 2021; Lu, 2012; Yi et al., 2014). In a longitudinal analysis of an Indonesian dataset, Lu found that left-behind adults (including left-behind women) had 37% more odds of experiencing hypertension (Lu, 2012). However, two studies reported positive impacts (Ali et al., 2017; Nwankwo & Govia, 2022) on migrant wives’ physical health. Ali et al. found that the incidence of chronic and other diseases was higher among non-migrant wives compared to migrant wives in a cross-sectional study in India (Ali et al., 2017). A mixed-methods study in Bangladesh reported both positive and negative impacts; they found that migrant wives had lower risk of undernutrition (anemia and underweight) but higher risk for excess adiposity (obesity, high body fat percentage, and waist circumference) compared to non-migrant wives (Sznajder et al., 2021). Whereas two quantitative studies reported no difference in physical health among migrant and non-migrant wives (Aghajanian et al., 2014; West et al., 2021). Aghajanian et al. elaborated that this was because the study community had a deep-rooted tradition of male migration, and hence acceptance on the part of migrant wives (Aghajanian et al., 2014).

The factors positively affecting physical health included: higher autonomy among migrant wives (Ali et al., 2017; Lei & Desai, 2021); better economic status/remittances (Ali et al., 2017; Lei & Desai, 2021; Sznajder et al., 2021); and higher food security (Sznajder et al., 2021). Based on a panel survey in India, Lei and Desai elaborated that for women in nuclear families, the negative health effect on the physical health of migrant wives was partially suppressed by women’s increased autonomy (Lei & Desai, 2021). The factors affecting physical health negatively among migrant wives included: longer duration of separation from spouse (Chen et al., 2015; Lu, 2012); low remittance (Lei & Desai, 2021); physical inactivity (Sznajder et al., 2021); higher income leading to increased purchase of ready-made food from the market (Sznajder et al., 2021); burden of increased household responsibilities including childcare (Huang et al., 2018), farm work (Huang et al., 2018), animal care (Lei & Desai, 2021) and handling a bank account (Lei & Desai, 2021). Findings also showed that with increased duration of separation, the physical disadvantage increased (Chen et al., 2015; Lu, 2012). Perhaps during short-term separation, the remittance sent by the absent spouse could aid better health (Chen et al., 2015).

3.3. Health-care accessibility

Five studies looked at health-care accessibility among migrant wives, all of which were conducted in Asia. All five studies concluded that migrant wives had better health-care accessibility than non-migrant wives (Gartaula et al., 2012; Green et al., 2019; Shwe et al., 2020; Thapa et al., 2019; West et al., 2021). A mixed-methods study in Nepal found that the antenatal check-up was significantly higher (88.3% vs. 83.3%) among migrant wives (Thapa et al., 2019). In terms of decision-making, migrant wives had higher autonomy to make decisions regarding their own healthcare (Green et al., 2019; Shwe et al., 2020) and reported increased access to health care if they were receiving direct remittances, especially if they were receiving remittances regularly (Green et al., 2019). Reduction of financial barriers was another reason for improved health-care accessibility among migrant wives (Thapa et al., 2019; West et al., 2021). West et al. found that everyday contact with husbands had a further positive effect on migrant wives’ health care access; however, migrant wives experienced a significant increase in family-related barriers such as being too busy to access healthcare (West et al., 2021).

3.4. Sexual and reproductive health

3.4.1. Family planning

Five studies focused on family planning among left-behind women; all five were based in Nepal. Regarding family planning communication with spouses, cross-sectional survey findings showed that left-behind women were less likely to discuss about family planning with partners compared with women with non-migrant partners (Hendrickson & Underwood, 2020; Shattuck et al., 2019). Factors negatively affecting communication regarding family planning included less overall communication with spouse, migration of spouse to a distant location and longer duration of separation (Hendrickson & Underwood, 2020). Qualitative findings further revealed that left-behind women usually put off communicating regarding family planning until their husbands returned or visited (Hendrickson et al., 2018, 2019). This could lead to unintended pregnancies and other undesirable consequences (Hendrickson et al., 2018). Left-behind women in Nepal reported using temporary family planning methods during their spouses’ visit (Hendrickson et al., 2018, 2019). In their cross-sectional study, Shattuck et al. found that migrant wives in Nepal more frequently reported the intention to become pregnant in the next year, had lower knowledge on male and female fertility, and were less likely to access reproductive health services compared to women who lived with their husbands (Shattuck et al., 2019). In contrast, migrant wives during qualitative interactions reported postponing pregnancies because their husbands were (going) away, with some reporting to have terminated pregnancies, and a few women reported difficulties in conceiving when their spouses finally returned for good (Thapa et al., 2019).

3.4.2. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

Six studies focused on STIs and/or Human Immuno-deficiency Virus (HIV)/Acquired Immuno-Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), out of which four were conducted in Asia and two in Africa. Left-behind women were more likely to suspect their partners of infidelity (Agadjanian et al., 2011; Agadjanian & Markosyan, 2017) and to worry about getting STIs/HIV from their partners than non-migrant spouses (Agadjanian et al., 2011; Agadjanian & Markosyan, 2017; Hughes et al., 2006). Migrant wives’ fear of contracting STIs were significantly affected by the economic success of men’s migration (Agadjanian et al., 2011), whether women themselves had extramarital partners (Agadjanian et al., 2011), and infrequent visit from partners (1-4 times a year) (Hughes et al., 2006). Some migrant wives perceived economic success as an ability for their husbands to pay for sex (Agadjanian et al., 2011) and therefore worried more about contracting STIs from them.

Spouses of migrants in Armenia were more likely talk to their partners about STI risks than spouses of non-migrants (Sevoyan & Agadjanian, 2015), whilst left-behind women in South Africa feared communicating their concerns regarding STI risks with spouses (Hughes et al., 2006). Also, suspicion of infidelity and concerns about contracting STIs did not translate to risk avoidance behaviours such as condom use when reunited (temporarily or permanently) with spouses (Agadjanian & Markosyan, 2017; Hughes et al., 2006). In both studies, authors argued that this gap between knowledge/awareness of risk of contracting HIV and action to prevent possible transmission could be explained by the prevalent gender inequality where the women were dependent financially on their husbands and were therefore not in a position to negotiate safe sexual practices (Agadjanian & Markosyan, 2017; Hughes et al., 2006).

Migrant wives were also more likely to report experiencing potential STI symptoms (Aghajanian et al., 2014; Sevoyan & Agadjanian, 2010) and STI diagnosis compared to non-migrant wives (Sevoyan & Agadjanian, 2010). Factors significantly and positively affecting experiencing STI symptoms included: increased household income (Sevoyan & Agadjanian, 2010) and urbanicity (Aghajanian et al., 2014). Aghajanian, Alihoseini and Thompson found that urban migrant wives reported experiencing STI symptoms significantly more often than urban non-migrant wives, indicating that urban male migrants may be engaging in risky sexual behaviour compared to rural male migrants (Aghajanian et al., 2014). Whereas factors positively affecting STI diagnosis included: increased household income (Sevoyan & Agadjanian, 2010) and duration of husband’s migration (Sevoyan & Agadjanian, 2010). In terms of help-seeking for STIs, women married to migrants were much less likely to seek healthcare for STI-like symptoms if they had not communicated to their husbands regarding these symptoms compared to women married to non-migrants (Sevoyan & Agadjanian, 2015), again indicating the power imbalance between left-behind who feared being abandoned and loss of financial security.

3.5. Other health-related issues

Mortality: Using a longitudinal panel dataset, Agadjanian et al. studied mortality among migrant and non-migrant wives in Mozambique (Agadjanian et al., 2021). They found that there was no significant difference in mortality among migrant and non-migrant wives. However, there was a significant different between mortality among migrant wives based on the migration success of their husbands; women married to less successful migrants had higher mortality risks than women married to successful migrants. Based on the remittances received by migrant-wives (objective success), mortality was lowest among women receiving remittances frequently, somewhat higher among those receiving them occasionally, and highest among those not receiving any remittances at all. The difference in mortality was even strikingly higher based on the perception of the migrant-wives of their husbands’ success (subjective) with mortality higher among wives who perceived their husbands working abroad to be less successful (Agadjanian et al., 2021). Marital separation and physical violence by husband significantly increased the risk of mortality while the number of children decreased the risk of mortality (Agadjanian et al., 2021).

Food security: A mixed-methods study in Nepal found that migration and remittances improved objective wellbeing of the left-behind women and their families by improving food and housing conditions (Gartaula et al., 2012). However, a study in Ghana found that migrant women reported food insecurity in the absence of their husbands as the reduced labour could mean decreased farming output (Wrigley-Asante & Agandin, 2015).

Alcohol/smoking: Thapa et al.’s study among women in Nepal concluded that migrant wives were significantly more likely to smoke in comparison to non-migrant wives, and while alcohol consumption was significantly higher among non-migrant wives, it was increasing among migrant wives (Thapa et al., 2019).

4. Discussion

In this systematic literature review, 33 studies explored the impact of migration on the health of women who remained behind. The major themes that emerged included: mental health; physical health; access to healthcare; and sexual and reproductive health (family planning/ STIs). In terms of mental, and sexual and reproductive health, findings showed that there were negative health consequences for women who remained behind, whereas findings on physical health are inconclusive with some studies showing better health among migrant wives comparted to non-migrant wives while others showing worse outcomes. In terms of healthcare accessibility however, migrant wives had a clear advantage. The major factors that appear to mediate the effect of being migrant wives on health were household income, increased responsibilities (e.g., childcare and farming), spousal and family relationships, and autonomy/decision-making. Additionally, the impact of spousal separation on health of left-behind women was found to intersect with the gendered disadvantage that women face in patriarchal settings prevalent in LMICs.

The most prominent impact on the health of left-behind women was on their mental health with almost all studies on the topic reporting that migrant wives had more depressive symptoms. International migrants are economically, socially and legally vulnerable in destination countries (Ushakov & Auliandri, 2020). Many workers, particularly low and semi-skilled migrants, face exploitative conditions, such as working for extremely long hours for below minimum wages (IOM, 2020). This situation of migrants naturally leads to their wives worrying for their safety and wellbeing (Bhurtyal, 2015; Debnath & Selim, 2009). Additionally, emotional seclusion (Bhurtyal, 2015; de Haas & van Rooij, 2010; Hena & Jahan, 2021; Singh, 2020), long periods of sexual abstinence (de Haas & van Rooij, 2010; Malik & Aftab, 2015), financial dependence on their husbands (de Haas & van Rooij, 2010) and the fear of being replaced by their husbands (Debnath & Selim, 2009; de Haas & van Rooij, 2010; Fernández-Sánchez et al., 2020; Roy & Nangia, 2005) complicated life for left-behind women. In conservative patriarchal settings such as South Asia, findings showed that left-behind women were often harassed by their male relatives and/or their husbands' male friends in the absence of their husbands (Debnath & Selim, 2009; Kakati, 2014; Kamal, 2020; Malik & Aftab, 2015); however, women were afraid to share this with their husbands or anyone else for fear that they will be blamed for this (Debnath & Selim, 2009; Kamal, 2020). Similar to our findings on sexual and reproductive health, a review on health of migrants in Nepal by Simkhada et al. found that left-behind women were at high risk of STIs due to unsafe sexual behaviour of their husbands and due to gender inequality pervasive in patriarchal Nepal, many women could not negotiate safe sex (using condoms) with husbands despite the desire (Simkhada et al., 2017). Similarly, Fernández-Sánchez et al. found that migrant wives were less likely to use contraceptives, less likely to discuss family planning with their husbands and were also prone to STIs (Fernández-Sánchez et al., 2020).

Our findings indicated a strong relationship between household income as a result of migration and the mental, physical, sexual and reproductive health, and healthcare access of migrant wives. Existing evidence shows that the effects of migration on health and general well-being of non-migrating household members vary according to the economic returns of migration (Agadjanian et al., 2021). Improved household income in migrant households meant improved food security, ability to afford healthcare (including private healthcare) and better living conditions (Das et al., 2020; Dicolen & Baconguis, 2020). However, economic success could affect health of migrant wives negatively as well by leading to lifestyle changes such as physical inactivity or regular purchase of relatively unhealthier foods such as fast foods from markets. On the other hand, if migrants are unable to send remittances regularly or sufficiently, this could again affect physical and mental health of migrant wives negatively. Left-behind women have the additional strain of making ends meet in the limited income (Hena & Jahan, 2021; Jain & Jayaram, 2022). Jain and Jayaram (2022) found in their study that women whose migrant husbands didn’t earn enough worked hard in farms to increase output and tried to earn additional cash through waged labour (Jain & Jayaram, 2022). Our findings also showed higher perceived and actual risk of STI among wives of economically successful migrants which migrant wives perceived as ability of their husbands to pay for sex.

Our findings highlight that increased workload could affect the physical and mental health, and healthcare access of migrant wives negatively. Many studies in the literature have discussed an increase in women’s workload in the absence of their spouses (Debnath & Selim, 2009; de Haas & van Rooij, 2010; Fakir & Abedin, 2020; Fernández-Sánchez et al., 2020; Kakati, 2014; Lokshin & Glinskaya, 2009; Lopez-Ekra et al., 2011; Roy & Nangia, 2005) as they become solely responsible for household chores, childcare, and other responsibilities from farming to handling finances leading to chronic physical and emotional fatigue. Singh (2020) in his study found that even women who lived in joint families complained of increased work burden (Singh, 2020).

Spousal and family relationships were also a key factor affecting health of migrant wives. Regular communication with spouses served as a protective factor for better mental health and improved healthcare access. Whereas prolonged separation from spouse, less communication and/or a strained marriage negatively impacted mental health and physical health of LBWs. There is also a major impact of spousal relationship on the SRH, causing women to worry of contracting STI and actually increasing their risk of contracting STIs and health care seeking. Existing studies have shown that left-behind women are disrespected and abused by family members in the absence of their husbands (Kadi, 2020; Singh, 2020). Similar to our findings, Singh (2020) found that disrespectful behaviour from in-laws/relatives, including domestic and sexual violence negatively affected the mental health of migrant wives (Singh, 2020).

Our findings also point to a positive relationship between autonomy/decision-making power of migrant wives and both their physical health and healthcare access. It was noted that in most patriarchal settings, especially if women live in nuclear families and become de-facto household heads, women’s autonomy and decision-making power may increase in the absence of their spouses (Debnath & Selim, 2009; Fakir & Abedin, 2020; Fernández-Sánchez et al., 2020). However, other studies found that there were negative consequences for women’s autonomy if they lived within the extended family households of their in-laws (de Haas & van Rooij, 2010; Fakir & Abedin, 2020; Kadi, 2020). Studies in Bangladesh found that husbands still maintained authority, and in some cases control, over their wives where husbands monitored and instructed their wives through regular phone conversations (Hena & Jahan, 2021; Kamal, 2020). While women's autonomy/decision-making power may increase in the absence of their husbands in patriarchal settings, and therefore enhance health-seeking behaviour, it might also have the opposite effect, where women's dependency on their husbands' income increases, and therefore they may not be in a position to make decisions regarding seeking healthcare as it is the husbands who make financial decisions (Sevoyan & Agadjanian, 2015). Therefore, whether left-behind women’s access to healthcare increased or not would depend on whether or not women’s autonomy and decision-making power increased in the absence of their spouses.

Policy/programme recommendations

The findings of this review expose the influence of patriarchal position which provides the canvas upon which the health and lives of left-behind women is situated. This review has illustrated that spousal separation due to migration has adverse consequences on the mental, physical and sexual and reproductive health of non-migrating spouses. Thus, it is imperative that governments of migrant sending as well as host countries target the health of left-behind women if the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) of providing good health and well-being (SDG Goal 3) and promoting responsible migration (SDG Target 10.7), while leaving no one behind, is to be realized (UN, 2015). Actions such as integrating components of migration health policy with mental health policy (Siriwardhana et al., 2015), encouraging family migration (Tong et al., 2019), making local support groups and counselling services available at the local health centre (Yi et al., 2014), and promoting improved communication between non-migrating spouses and migrant partners (Huang et al., 2018; Lu, 2012) should be initiated. It is also clear that a lack of labour market opportunities creates and maintains unintended consequences for health budgets and wider spending by governments on the wellbeing of their citizens. This review lends further support to the argument that national governments should improve job prospects and labour market opportunities in their own country so that husband and wives do not have to choose separation to enhance their income. (Bhurtyal & Wasti, 2021; Thapa et al., 2019)

Acknowledging mental health problems among migrant wives, the governments in sending countries, together with non-government organizations should organize mental health screening programs for early diagnosis and treatment of mental health problems (Bhurtyal & Wasti, 2021) and counselling/support programs (Arokkiaraj et al., 2021; Bhurtyal & Wasti, 2021; Wrigley-Asante & Agandin, 2015) to enable migrant wives to cope with emotional problems in the absence of their husbands. Governments and non-governments programs should also organize counselling sessions for migrant wives that include fertility, family planning, and STI prevention, including safe sex/use of condoms. Counselling sessions could also include economic aspects such as skills training programs and linkage with markets to enable women to contribute to household income as well as become financially independent (Wrigley-Asante and Agandin, 2015; Arokkiaraj, Kaushik and Rajan, 2021). Community sensitization programs should be organized to address patriarchal attitudes (Wrigley-Asante & Agandin, 2015) and enable family support.

Future Research

Although, mental health and sexual and reproductive health among left-behind has been explored to some extent, more studies of quantitative as well as qualitative nature are required to build a stronger evidence base. Longitudinal and prospective cohort studies to establish causation and impact of migration on wellbeing and mental health of family members (Siriwardhana et al., 2015) and qualitative studies to understand how mental health of non-migrating women is impacted and what factors affect mental health are needed. Studies are also needed to ascertain the risk of STIs among migrant wives (Sevoyan & Agadjanian, 2010) in general and sub-groups including urban migrant wives (Aghajanian et al., 2014) and to explore unintended pregnancies, abortions, etc. among left-behind women. Similarly, more studies using diverse and strong methods are needed to determine the overall physical health impact on migrant wives. We recommend more studies exploring the impact autonomy (Shwe et al., 2020), income and increased responsibilities, on migrant’s wives’ health, particularly, on how it could affect physical health.

Studies should also explore health effects among different sub-group of migrant wives (e.g. on the basis of age groups and urban/rural areas). Future studies should make comparisons by destination, duration and frequency of migration, and also consider the cross-sectionalism of migration and health with feminism/gender concepts (West et al., 2021). Underexplored areas such as impact on marital relationship with spouse and how this affects their health, non-migrant women’s vulnerability to violence, and impact of remittance on health and nutrition should be studied among other issues. Finally, whilst we recognise men form a smaller cohort of those who are left behind, it is important that their voices and experiences are heard.

Our review also has some limitations. While including grey literature, particularly for an underexplored topic such as left-behind women’s health would have provided a more comprehensive picture of the study issue, we included only empirical studies due to time constraints and considering the strength of peer-reviewed studies (Paez, 2017). Unpublished studies and articles in languages other than English were not included in this review. The findings of our review focus only on migrant wives from LMICs. Another limitation is that although nearly half of international migrants globally are women and women’s migration increasing in LMICs (IOM, 2020), the perspective of left-behind men is not included in this review.

5. Conclusion

Existing studies clearly indicate that there are physical, mental and reproductive health implications for non-migrating spouses of international labour migrants. While remittance increases objective wellbeing in terms of food security, housing and healthcare access, the increased workload in the absence of their spouses, the prolonged separation and resultant lack of a sex life and loss of emotional intimacy leads to physical and emotional stress. Therefore, going forward, a family approach to migration should be encouraged. In LMICs, governments should take initiatives to provide employment opportunities in their home countries so that migration as an unavoidable livelihood strategy can be avoided.

Acknowledgements

We thank the School of Human and Health Sciences, University of Huddersfield for funding the PhD degree of the first author.

List of references

- Agadjanian, V., Arnaldo, C., & Cau, B. (2011). Health Costs of Wealth Gains: Labor Migration and Perceptions of HIV/AIDS Risks in Mozambique. Social Forces, 89(4), 1097–1117. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/89.4.1097

- Agadjanian, V., Hayford, S. R., & Jansen, N. A. (2021). Men’s migration and women’s mortality in rural Mozambique. Social Science and Medicine, 270, 113519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113519

- Agadjanian, V., & Markosyan, K. (2017). Male labor migration, patriarchy, and the awareness-behavior gap: HIV risks and prevention among migrants’ wives in Armenia. AIDS CARE, 29(6), 705–710.

- Aghajanian, A., Alihoseini, J., & Thompson, V. (2014). Husband’s Circular Migration and the Status of Women left behind in Lamerd District, Iran: A pilot study. Asian Population Studies, 10(1), 40–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2013.840082

- Ali, I., Bhagat, R. B., Shankar, G., & Verma, R. K. (2017). Morbidity differential among emigrants’ and non-emigrants’ wives in Kerala, India. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 13(3), 346–359. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMHSC-02-2015-0006

- Arokkiaraj, H., Kaushik, A., & Rajan, S. (2021). Effects of International Male Migration on Wives Left Behind in Rural Tamil Nadu. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 28(2), 228–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971521521997964

- Aryal, N., Regmi, P. R., van Teijlingen, E., Trenoweth, S., Adhikary, P., & Simkhada, P. (2020). The impact of spousal migration on the mental health of nepali women: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041292

- Bhurtyal, Y. (2015). Effects of male international migration on wives left behind in Nepal. http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/11677/1/Effects%20of%20male%20international%20migration%20on%20wives%20left%20behind%20in%20Nepal.docx

- Bhurtyal, Y., & Wasti, S. (2021). Effects of Male International Migration on Mental Health of Wives Left Behind in Nepal. Journal of Manmohan Memorial Institute, 7(1), 60–72. https://doi.org/10.3126/jmmihs.v7i1.43151

- Boyd, M., & Grieco, E. (2003). Women and migration: Incorporating gender into international migration theory. Migration Information Source, 1(35), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/mcs.1220010102

- CASP. (2018). Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: Qualitative Checklist (pp. 1–6). https://ktpathways.ca/system/files/resources/2019-02/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf

- Chen, F., Liu, H., Vikram, K., & Guo, Y. (2015). For Better or Worse: The Health Implications of Marriage Separation Due to Migration in Rural China. Demography, 52(4), 1321–1343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0399-9

- Das, P., Saha, J., & Chouhan, P. (2020). Effects of labor out-migration on socio-economic set-up at the place of origin: Evidence from rural India. Children and Youth Services Review, 119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105512

- Debnath, P., & Selim, N. (2009). Impact of short term male migration on their wives left behind: A case study of Bangladesh. In Gender and Labour Migration in Asia (pp. 122–151).

- de Haas, H., & van Rooij, A. (2010). Migration as emancipation? The impact of internal and international migration on the position of women left behind in rural morocco. Oxford Development Studies, 38(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600810903551603

- Dicolen, E., & Baconguis, R. (2020). International Migration and the Empowerment of Women Left Behind. Journal of Saemaulogy, 5(1), 103–141. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Emely-Dicolen-2/publication/346301872_International_Migration_and_the_Empowerment_of_Women_Left_Behind/links/5fbdbb9892851c933f57b93a/International-Migration-and-the-Empowerment-of-Women-Left-Behind.pdf

- Fakir, A. M. S., & Abedin, N. (2020). Empowered by Absence: Does Male Out-migration Empower Female Household Heads Left Behind? Journal of International Migration and Integration, 22, 503–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-019-00754-0

- Fernández-Sánchez, H., Salma, J., Márquez-Vargas, P. M., & Salami, B. (2020). Left-Behind Women in the Context of International Migration: A Scoping Review. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 31(6), 606–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659620935962

- Gartaula, H. N., Visser, L., & Niehof, A. (2012). Socio-Cultural Dispositions and Wellbeing of the Women Left Behind: A Case of Migrant Households in Nepal. Social Indicators Research, 108(3), 401–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9883-9

- Green, S. H., Wang, C., Ballakrishnen, S. S., Brueckner, H., & Bearman, P. (2019). Patterned remittances enhance women’s health-related autonomy. SSM - Population Health, 9(January), 100370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100370

- Hena, A., & Jahan, S. (2021). Negotiated Survival: Male Out-Migration and ‘The Challenges and Coping Strategies’ of Wives’ Left Behind in Rural Bangladesh. Researchgate.Net, 26(7), 25. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-2607032531

- Hendrickson, Z. M., Lohani, S., Thapaliya Shrestha, B., & Underwood, C. R. (2018). Talking about reproduction with a migrating spouse: Women’s experiences in Dhading, Nepal. Health Care for Women International, 39(11), 1234–1258.

- Hendrickson, Z. M., Owczarzak, J., Lohani, S., Thapaliya Shrestha, B., & Underwood, C. R. (2019). The (re) productive work of labour migration: the reproductive lives of women with an absent spouse in the central hill region of Nepal. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 21(684–700).

- Hendrickson, Z. M., & Underwood, C. R. (2020). Intimate Communication across Borders: Spousal Labor Migration and Recent Partner Communication about Family Planning in Nepal. Marriage and Family Review, 56(5), 470–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2020.1728004

- Hondagneu-Sotelo, P. (2000). Feminism and MIgration. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 571(1), 107–120.

- Hong, Q., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., Rousseau, M.-C., & Vedel, I. (2018). Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018: User guide. In McGill (pp. 1–11). http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf%0A http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/

- Huang, H., Liu, S., Cui, X., Zhang, J., & Wu, H. (2018). Factors associated with quality of life among married women in rural China: a cross-sectional study. Quality of Life Research, 27(12), 3255–3263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1944-y

- Hughes, G. D., Hoyo, C., & Puoane, T. R. (2006). Fear of sexually transmitted infections among women with male migrant partners - Relationship to oscillatory migration pattern and risk-avoidance behaviour. South African Medical Journal, 96(5), 434–438. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.1130

- IOM. (2019). Migration in Nepal: A Country Profile 2019.

- IOM. (2020). World Migration Report 2020. In European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook. https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2020

- Jain, P., & Jayaram, N. (2022). The intimate subsidies of left-behind women of migrant households in western India. Gender, Place and Culture. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2022.2042209

- Jin, Y., Qin, Q., Zhan, S., Yu, X., Liang, L., & Huang, F. (2016). Depressive symptoms were prevalent among left-behind women in Ma’anshan, China. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 204(3), 226–232. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000444

- Kadi, Y. (2020). Echoes of Home: The Impact of Male Migration on Left-Behind Women, Tadla-Azilal Villages as a Case Study. Identityanddifference.Org, I. http://identityanddifference.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Article-6-Yousra-Kadi-article-corrected.pdf

- Kakati, B. K. (2014). Out-Migration and Its Bearing on Left-Behind Woman: Case in a Jharkhand village. Social Change and Development, XI (2), 83–89. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331872408

- Kamal, M. (2020). Wives left behind : A study of the impacts of men ’ s international labour migration on their wives in Bangladesh Marzana Kamal A thesis submitted to the School of History, Philosophy and Social Sciences, for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociol.

- Lei, L., & Desai, S. (2021). Male out-migration and the health of left-behind wives in India: The roles of remittances, household responsibilities, and autonomy. Social Science & Medicine, 280, 113982. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953621003142

- Lokshin, M., & Glinskaya, E. (2009). The effect of male migration on employment patterns of women in Nepal. World Bank Economic Review, 23(3), 481–507. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhp011

- Lopez-Ekra, S., Aghazarm, C., Kötter, H., & Mollard, B. (2011). The impact of remittances on gender roles and opportunities for children in recipient families: Research from the international organization for migration. Gender and Development, 19(1), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2011.554025

- Lu, Y. (2012). Household migration, social support, and psychosocial health: The perspective from migrant-sending areas. Social Science and Medicine, 74(2), 135–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.020

- Malik, M. M., & Aftab, R. (2015). Psychosocial Impact of Male Migration on the Women Left Behind. Biannual Journal of Gender and Social Issues, 14(1), 43–67.

- McAuliffe, M., & Triandafyllidou, A. (2021). World Migration Report 2022.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., Altman, D., Antes, G., Atkins, D., Barbour, V., Barrowman, N., Berlin, J. A., Clark, J., Clarke, M., Cook, D., D’Amico, R., Deeks, J. J., Devereaux, P. J., Dickersin, K., Egger, M., Ernst, E., … Tugwell, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Moola, S., Munn, Z., Tufanaru, C., Aromataris, E., Sears, K., Sfetchu, R., Currie, M., Qureshi, R., Mattis, P., LIsy, K., & Mu, P.-F. (2020). Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis (pp. 1–5). Joanna Briggs Institute. https://joannabriggs.org/critical_appraisal_tools

- Nawyn, S. J. (2010). Gender and Migration: Integrating Feminist Theory into Migration Studies. Sociology Compass, 4(9), 749–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2010.00318.x

- Nikoloski, Z., Zhang, A., Hopkin, G., & Mossialos, E. (2019). Self-reported symptoms of depression among Chinese rural-to-urban migrants and left-behind family members. JAMA Network Open, 2(5), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3355

- Nwankwo, E. M., & Govia, I. O. (2022). Migration and the Health of Non-migrant Family: Findings from the Jamaica Return (ed) Migrants Study. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 24(3), 689–704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01239-y

- Paez, A. (2017). Gray literature: An important resource in systematic reviews. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine, 10(3), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12266

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., Britten, N., Roen, K., & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme, 1(1), b92. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233866356_Guidance_on_the_conduct_of_narrative_synthesis_in_systematic_reviews_A_product_from_the_ESRC_Methods_Programme?channel=doi&linkId=02e7e5231e8f3a6183000000&showFulltext=true%0A. https://www.researchgate.net/

- Roy, A. K., & Nangia, P. (2005). Impact of Male Out-migration on Health Status of Left behind Wives-A Study of Bihar, India. International Union for the Scientific Study of Population Meetinga, 1–22. http://www.who.int/about/definition/en/

- Sevoyan, A., & Agadjanian, V. (2010). Male migration, women left behind, and sexually transmitted diseases in Armenia. International Migration Review, 44(2), 354–375. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2010.00809.x

- Sevoyan, A., & Agadjanian, V. (2015). Male labour migration, spousal communication, and STI treatment in Armenia. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 17(3), 296–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2014.936042

- Shattuck, D., Wasti, S. P., Limbu, N., Chipanta, N. S., & Riley, C. (2019). Men on the move and the wives left behind: the impact of migration on family planning in Nepal. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 27(1), 248–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2019.1647398

- Shwe, W. W., Jampaklay, A., Chamratrithirong, A., & Thaweesit, S. (2020). Husband’s international migration: Decision-making autonomy among left-behind wives in rural area of central Myanmar. Journal of Health Research, 34(1), 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHR-03-2019-0040

- Simkhada, P. P., Regmi, P. R., van Teijlingen, E., & Aryal, N. (2017). Identifying the gaps in Nepalese migrant workers’ health and well-being: A review of the literature. Journal of Travel Medicine, 24(4), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/tax021

- Singh, A. (2020). Male out-migration and its psychological bearing on left behind women: A case study of a poor farming community of bundelkhand village of UP, India. Bulletin of Pure & Applied Sciences- Geology, 39f (1), 94. https://doi.org/10.5958/2320-3234.2020.00010.4

- Siriwardhana, C., Wickramage, K., Siribaddana, S., Vidanapathirana, P., Jayasekara, B., Weerawarna, S., Pannala, G., Adikari, A., Jayaweera, K., Pieris, S., & Sumathipala, A. (2015). Common mental disorders among adult members of ‘left-behind’ international migrant worker families in Sri Lanka Global Health. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1632-6

- Sznajder, K., Wander, K., Mattison, S., Medina-Romero, E., Alam, N., Raqib, R., Kumar, A., Haque, F., Blumenfield, T., & Shenk, M. (2021). Labor migration is associated with lower rates of underweight and higher rates of obesity among left-behind wives in rural Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. Globalization, 17(81), 1–11. https://globalizationandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12992-021-00712-5

- Thapa, N., Paudel, M., Guragain, A. M., Thapa, P., Puri, R., Thapa, P., Aryal, K. K., Paudel, B. K., Thapa, R., & Stray-Pedersen, B. (2019). Status of migration and socio-reproductive impacts on migrants and their families left behind in Nepal. Migration and Development, 8(3), 394–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2019.1567097

- Tong, Y., Chen, & B Shu. (n.d.). Intimacy Lost or Autonomy Gained? Spousal migration and Left-behind Wives’ Subjective Well-being in Rural China. Pdfs.Semanticscholar.Org. Retrieved 17 November 2020, from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/eef0/694d96082a3daf16a5579256e8e9c9b806da.pdf

- Tong, Y., Chen, F., & Shu, B. (2019). Spousal migration and married adults’ psychological distress in rural China: The roles of intimacy, autonomy and responsibility. Social Science Research, 83(May), 102312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2019.06.003

- Toyota, M., Yeoh, B. S. A., & Nguyen, L. (2007). Editorial introduction: Bringing the ‘left behind’ back into view in Asia: A framework for understanding the ‘migration-left behind nexus’. Population, Space and Place, 13(3), 157–161. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.433

- UN. (2015). Sustainable Development: The 17 Goals.

- UNDP. (2009). Human development report 2009: ‘Overcoming barriers: Human mobility and development’.

- Ushakov, D., & Auliandri, T. A. (2020). International Labor Migration in South Asia: Current Situation and the Problems of Efficient National Regulation. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 753(8). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/753/8/082024

- West, H. S., Robbins, M. E., Moucheraud, C., Razzaque, A., & Kuhn, R. (2021). Effects of spousal migration on access to healthcare for women left behind: A cross-sectional follow-up study. PLoS ONE, 16(12), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260219

- Wrigley-Asante, C., & Agandin, J. B. A. (2015). From Sunrise to Sunset: Male Out-Migration and Its Effect on Left-Behind Women in the Builsa District of Ghana. Gender Issues, 32(3), 184–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12147-015-9139-0

- Yi, J., Zhong, B., & Yao, S. (2014). Health-related quality of life and influencing factors among rural left-behind wives in Liuyang, China. BMC Women’s Health, 14(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-14-67

- Zimmerman, C., Kiss, L., & Hossain, M. (2011). Migration and Health: A Framework for 21st Century Policy-Making. PLoS Medicine, 8(5), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001034

Open Peer Review