- SN

1,031

121

11

Field

Business, Management and Accounting

Subfield

Tourism, Leisure and Hospitality Management

Politics of Representation in Rural Tourism Micro-Entrepreneurship

Affiliation

Abstract

Despite a substantial body of research on representational politics pertaining to Oriental destinations, the promotional strategies for rural destinations targeting urban visitors remain under-studied. This research examines perceptions of rural existence among tourism microentrepreneurs and their potential urban visitors. Using the visual Q methodology, participants interpreted images from North Carolina’s Piedmont region, that revealed four distinct perceptions of rural life: pastoral, small-scale and healthy, peaceful, and productive. This investigation sheds light on the interplay of representations between urban and rural groups, offering insights into intricacies of rural tourism marketing.

Correspondence: papers@team.qeios.com — Qeios will forward to the authors

Introduction

Historically, American literature and media have often depicted rural socio-environmental geographies negatively, portraying inhabitants as uncivilized and primitive. This perspective is evident in works by authors like William Byrd II, William Gilmore Simms, and Mark Twain, as well as in recent reality TV shows like "Rat Bastards" and "Duck Dynasty" (Roggenkamp, 2008). Such characterizations persistently shape modern narratives, portraying rural spaces as backward, industrious, and idyllic cultural and natural repositories, a contrast to the actual complexities of contemporary rural life (Woods, 2017).

Global polarization, primarily driven by the notion of Otherness, leads to considerable sociocultural, economic, and environmental imbalances. Prior studies have extensively explored the consequences of these negative depictions on formerly colonized regions and minority communities, contending that they perpetuate the dominance of Western philosophies over the Orient (Echtner & Prasad, 2003; Jafari & Scott, 2014).

In postcolonial ideologies, Othering sustains disparities, perpetuating colonialism on marginalized societies (Chambers & Buzinde, 2015). In rural tourism, postcolonial dynamics often reenact historical dominance, with urban visitors as colonizers and rural inhabitants as the colonized Other (Ashcroft et al., 2002). These socio-political geographies shape portrayals, creating a politics of representation that defines who has the power to represent and who becomes the subject (Bandyopadhyay & Morais, 2005).

Literature on tourism and representation often focuses on East-West geopolitical polarization, leaving a gap in understanding a region's internal rural-urban dynamics (Fulkerson & Thomas, 2013). Rural individuals in tourism media are also underexplored (Wijngaarden, 2016). Gössling et al. (2015) and argue these gaps maintain power imbalances, urging more nuanced investigations into rural representation in tourism.

In the context of rural tourism, urban cultural and economic superiority often leads to the exploitation of rural counterparts, who are depicted as socio-culturally stagnant and ill-adjusted to modern socio-economic systems (Roggenkamp, 2008). Tourist expectations of rural destinations are majorly influenced by media products, such as print and online magazines, brochures, and videos. Often, these are meticulously crafted by a profit-driven tourism industry with minimal or no community involvement (Morgan & Pritchard, 1998). The advent of social media and technologies such as virtual reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) has begun to shift the balance of power somewhat, providing a platform for rural inhabitants to directly share their experiences and narratives (Tussyadiah & Fesenmaier, 2009; Saedi & Rice, 2020). Despite this shift, the discourse within these platforms often remains dominated by the perspectives of the industry and urban visitors, limiting the extent to which they can challenge prevailing stereotypes.

The gap between representation and reality poses severe consequences, causing identity erosion and continuous pressure on rural communities to fulfill tourist expectations (Wei, Qian & Sun, 2018). Rural tourism microentrepreneurs, offering products with rural charm, are particularly vulnerable to these dynamics (Ferreira et al., 2015).

Microentrepreneurs utilize tourism for self-emancipation, employing various self-representation strategies to challenge prevailing narratives (Maoz, 2006; Wang & Morais, 2014). Nazariadli et al. (2019a) documented instances where they created authentic images for destination marketing. Nevertheless, their attempts to contest stereotypes are frequently overshadowed by formal sector marketing, perpetuating a continuous cycle of representation (Jørgensen & Phillips, 2002).

This research aims to fill this gap by employing the Q methodology to interpret perspectives on rural region representation in North Carolina as tourism destinations. It scrutinizes the viewpoints of rural tourism microentrepreneurs and potential urban visitors, addressing two key research questions:

- RQ1: What shared perspectives exist on visual representation and rural life among rural tourism microentrepreneurs and their potential urban visitors?

- RQ2: What divergent perspectives emerge in the visual representation of rural life between rural tourism microentrepreneurs and potential urban visitors?

This research explores shared and divergent perspectives to enhance our understanding of representation dynamics in rural tourism. It seeks to uncover how colonial narratives of domination and subjugation persist or are challenged in the current tourism context (Salazar, 2012). The study aims to empower rural tourism microentrepreneurs in authentically representing their identities, making a substantial contribution to the broader discourse on representation politics. By amplifying the voices of often overlooked microentrepreneurs, it provides valuable insights for policy and practice.

Theoretical Background

This study's analytical framework rests on Postcolonialism and Orientalism. Postcolonialism critiques cultural legacies of colonialism, providing a lens for dissecting power dynamics and cultural identity representations in tourism (Hall & Tucker, 2004). Similarly, Said's (1978) Orientalism discusses Western superiority over the 'Orient.' In rural tourism, this can extend to Urbannormativity, where urban identities dominate rural ones, resulting in the 'othering' of rural communities (Fulkerson & Thomas, 2013).

Microentrepreneurs, holding both resident and stakeholder roles in the tourism industry, uniquely challenge Urbannormative discourse. Their dual role is pivotal in promoting local communities to attract tourists, contributing an authentic narrative to the broader discourse of rural tourism (Ferreira et al., 2015; Nazariadli et al., 2019a).

From Discourse of Orientalism to Discourse of Tourism Media

Discourse, a structured system of meaning, shapes our perception of the social world, providing an organized mode of reasoning. It wields power by influencing knowledge creation, emphasizing certain voices, and prioritizing specific interests (Yan & Santos, 2009). Said (1978) coined Orientalism to depict a discourse underpinning the West's hegemony over the East. This discourse defines the East as the Other, inferior to the culturally, politically, and economically dominant West.

Said (1978) argued that the Oriental, encompassing people, culture, or religion, is an illusion but remains Orientalized. This symbolism portrays the West as advanced, masculine, normative, and rational, while the East is seen as backward, cunning, mysterious, exotic, and irrational. Orientalist discourse justifies the West's exploitation, colonization, and civilization of the East, masking it as benefaction and portraying the East as incapable of self-care, perpetually reliant on the white man (Echtner & Prasad, 2003).

Studies extensively probe tourism's neocolonial impact on destinations, emphasizing representational techniques. Tourism media disseminates skewed knowledge, subjugating misrepresented locals. Consequently, locals conform to externally imposed expectations rather than shaping authentic discourses reflecting their realities and serving their interests (Chambers & Buzinde, 2015).

Jenkins’ (2003) "representational loop" highlights travel media's role in sustaining stereotypes. Morgan et al. (2019) echo this, noting mainstream tourism rarely challenges or deconstructs these images. This perpetuates a loop that reconstructs, negotiates, and reinforces depictions, hindering rural populations from effectively challenging them (Yan & Santos, 2009). The struggle for power to represent and narrate instigates a battle between the representer and the represented.

The evolution of tourism media discourse in the digital age is noteworthy. Lugosi et al. (2020) assert that digital media alters the co-creation of tourist experiences, challenging traditional discourses in tourism representation. Similarly, the surge of social media and user-generated content empowers the 'represented,' enabling them to contest traditional representations (Munar & Jacobsen, 2014).

From Self-Orientalism to Self-Urbannormativization

To lure international tourists, Oman's Ministry of Tourism markets the country as exceptionally Oriental and exotic, labeling it the most beautiful in the Middle East. This depiction renders Omanis as static, deeply rooted in the past, and hospitable to potential international visitors (Feighery, 2012). Similarly, the Chinese government engages in self-Orientalism through "China Forever" tourism commercials, creating a mystified image for the Western gaze. However, Hong Kong, as per Zhang et al. (2015), leverages its colonial history to establish a distinct identity from mainland China. These intentional self-Orientalist portrayals arise from various motivations.

Traditionally focused on the Western Occident and Eastern Orient (Said, 1978), Orientalism can manifest within a single country as Internal Orientalism (Jansson, 2005). Examples include Schein's (1997) study on internal Orientalism in China and Jansson's (2005) exploration of a similar dynamic between the American North and South.

Self-orientalism and internal Orientalism combine, yielding Urbannormativity (Fulkerson & Thomas, 2013). Urbannormativity places urban norms at the core, pushing rural norms to the periphery (Seale, 2013). Rural communities commodify cultural assets for urban markets, seeking profit from tourism while conserving culture. Urbannormativity becomes self-Urbannormativization when marginalized communities internalize it, tacitly accepting urban norms.

Rural individuals are characterized as socially inept, resigned to hardship (Bell, 2006). Their behaviors are sometimes exploited for amusement or to enhance urban fantasies about rural areas. However, as argued by Halfacree (2017), these representations oversimplify the rural-urban dichotomy, overlooking the diverse realities and complexities inherent in both rural and urban life. Media often illustrates rural spaces as strange, stagnant, insular, underdeveloped, depopulating, aging, and desolate (Cloke, 2006). Yet, Woods (2017) posits rural communities can challenge and reconfigure these discourses, articulating their own narratives within the context of tourism.

Rural Tourism, Microentrepreneurship, and Challenging Urbannormativity

Microentrepreneurs in rural communities can challenge and reshape Urbannormative discourse in rural tourism. Their deep connections within the community and understanding of cultural nuances and the broader tourism industry allow them to counter prevailing representations (Ferreira et al., 2015; Nazariadli et al., 2019a). Dangi and Jamal (2016) suggest microentrepreneurs act as catalysts for sustainable development, contributing to economic growth, social, and environmental sustainability of rural areas. This aligns with the growing sustainable tourism discourse, emphasizing conservation and local engagement (Dodds & Butler, 2019).

Pursuit of sustainable tourism often requires reevaluating traditional representations and power structures. This sustainability lens enables a more balanced representation of rural communities, positioning them as active participants, not just passive subjects in tourism narratives (Torres & Momsen, 2011). Echoing this, Lähdesmäki et al. (2019) emphasize narratives by local agents, like microentrepreneurs, reshaping power dynamics in the tourism industry. They propose these local narratives profoundly influence how tourists perceive and engage with rural communities, altering the rural tourism landscape.

Methods

Q methodology, a social constructionist approach, is ideal for exploring and contrasting viewpoints among people with varying empowerment levels (Brown, 2005; Stainton Rogers, 1995). This study used Q methodology to identify mental models in socio-cultural rural geographies in North Carolina’s piedmont region, USA. Q methodology is useful in tourism, e.g., in segmentation studies and understanding residents’ perspectives on cultural representation and identity (Mokry & Dufek, 2014).

Q methodology involves participants (P-set) rank-ordering a research stimuli set (Q sample), typically composed of statements or images on a symmetrical distribution grid (Brown, 1980). Each Q item in the sample represents broader opinions known as the concourse of communication (COC) (Ramlo, 2015). Researchers interview participants post-sorting to uncover thoughts about Q items and their placements on the grid. For this study, we used Q sample images of rural Piedmont North Carolina from rural tourism microentrepreneurs via autophotography (Nazariadli et al., 2019a).

Study Setting and the P-Set

The P-set included rural tourism microentrepreneurs from North Carolina’s Piedmont region and urban residents from the Southeastern region of the USA. We chose 40 Q items, within the recommended 40-60 range (Brown, 1980) to prevent fatigue and enhance judgmental capability. In Q methodology, the P-set size should be equal or less than the number of Q items. We aimed for 20 urban and 20 rural participants, forming a P-set of 40. To capture region-specific opinions, we sought participants from geographically diverse areas (McKeown & Thomas, 2013).

Rural participants were from a sample of microentrepreneurs in a longitudinal participatory action research project (People-First Tourism) ranging from months to five years. Urban participants were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk), an online marketplace (Nazariadli et al., 2017a). The task, study details, inclusion criteria (urban North Carolinian), and the $1.50 incentive were posted on the MTurk website.

We verified urban and rural residency for the MTurk urban sample and rural participants using www.ruralhealthinfo.org, referencing the 2010 Census. The Census categorizes urban geographies as "urbanized areas" (population > 50,000), "urban clusters" (2,500 < population < 50,000), and "rural areas" (population < 2,500). Additionally, we used a four-item, 5-point Likert scale questionnaire, adapted from Krok-Schoen et al. (2015), to identify participants with higher/lower rural social identity (RSI).

Data Collection

Before administering a Q-method survey with visual Q items (referred to as a VQ survey) to the P-set, certain initial steps are necessary. These involve grid design and Q-item sampling from a concourse of communication (COC). To collect data from both urban and rural participants, this study used the VQMethod online research tool (Nazariadli, 2017c), with a composite reliability of r = 0.88 (Nazariadli et al., 2019b).

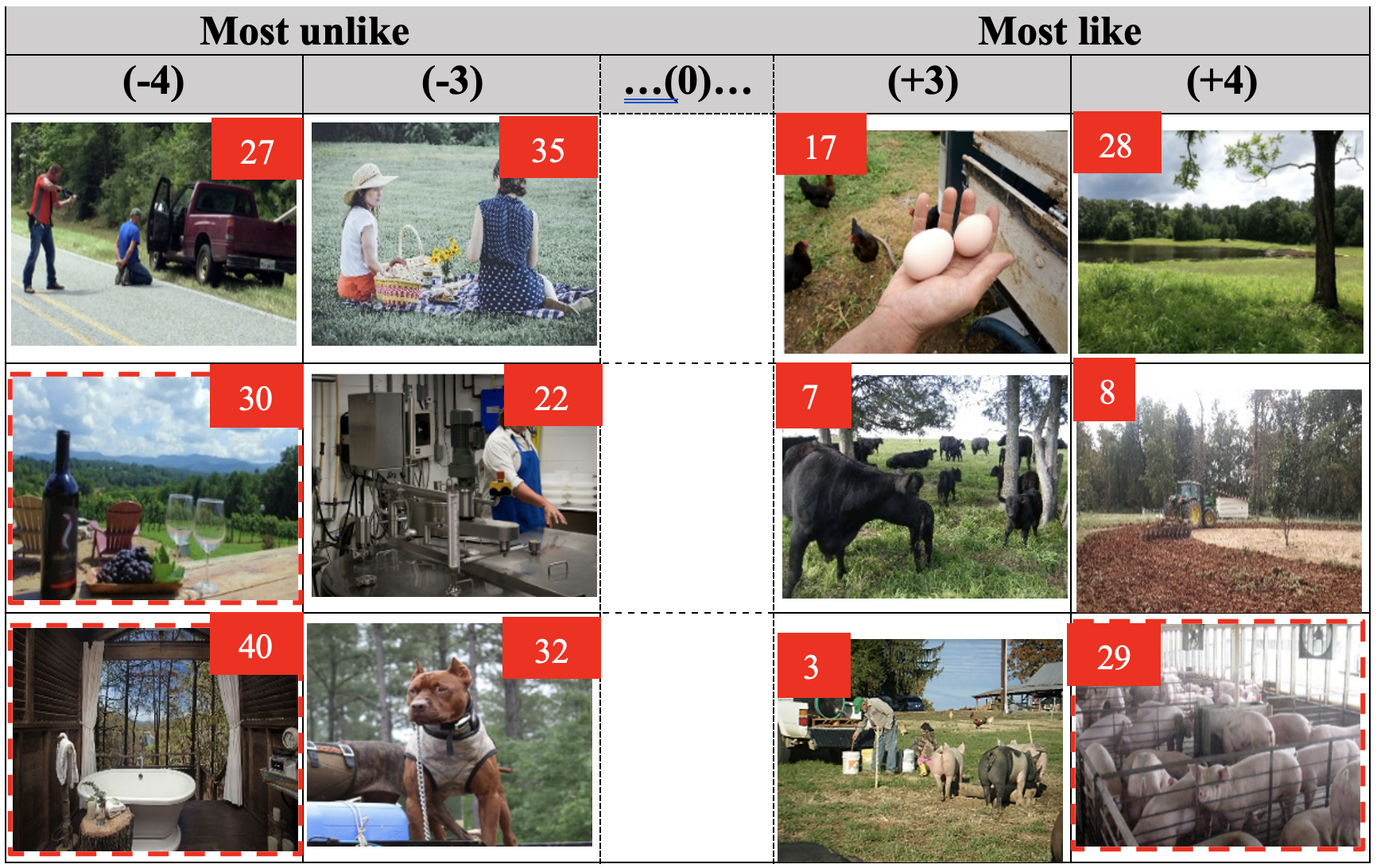

The grid's range depends on the number of Q items (-4 to +4 for 40-50 Q items) (Paige & Morin, 2016). This study used a -4 to +4 range, maintaining a normal distribution. As noted, the reasons for extreme thoughts are probed by selecting Q items to the grid edges. Participants might provide less information in writing than verbally, so a platykurtic grid design was used, placing more Q items at the grid ends (3 on each side). This approach elicited more images for subsequent participant explanation (Figure 1).

The Concourse of Communication (COC) originated from a pool of images in a previous study (Nazariadli et al., 2019a). In this study, 13 different rural tourism microentrepreneurs from Piedmont, North Carolina, took photos representing aspects of rural life for potential urban visitors. The study's COC included 130 images.

Following this, we used a structured deductive Q sampling method to select a representative Q sample of 40 images, preventing under- or over-sampling of opinions (Paige & Morin, 2016). Two attributes aligned with the theoretical foundations were considered: Urbannormative and anti-Urbannormative. Thematic analysis of 130 photos, agreed upon by two experts familiar with Urbannormative ideology, revealed five binary levels: systematic work - unsystematic work, disconnectedness with nature - connectedness with nature, productive - idyllic, modern/forward – primitive/backward, and peaceful - intimidating. Thus, a 2(attribute) × 5(level) factorial design was developed, generating ten matrix cells. With 40 Q items, we aimed to assign four photos per matrix cell.

Whittling down 130 photos to 40 required three steps. Firstly, discarding low-quality or identifiable images reduced the count to 112. Secondly, we performed content validity analysis, where three experts rated photos using a 1-item, 4-point Likert scale question (0 = “not relevant to (anti) Urbannormativity,” 4 = “highly relevant to the (anti) Urbannormativity”). The content validity index was calculated by summing raters who rated the image 3 or 4, then dividing by the total number of raters (Paige & Morin, 2016). Sixty-four items surpassed a content validity index of 0.80 and were placed into corresponding matrix cells.

The final 40 images were uploaded to the VQMethod website (Nazariadli, 2017c). Each image received an identifying number to record Q-sort patterns alongside corresponding numbers. Figure 2 displays the 40 images representing Urbannormative and anti- Urbannormative.

Data Elicitation

An anonymous link to the VQ Survey was emailed to rural participants. For potential urban participants, the survey link, with related descriptions, was posted on the MTurk website. After reading the research brief and approving their consent for the VQ survey, participants went through five steps (McKeown & Thomas, 2013). Step 1 involved familiarization with Q items and the research scope. In Step 2 (pre-sort), participants organized their mindset about image similarity or dissimilarity to rural Piedmont, NC by dragging and dropping 40 images into boxes labeled “Most Like,” “Most Unlike,” and “Neutral” (Figure 3). Then, they proceeded to Step 3 (Q sorting) to spread out images on a broader spectrum in a symmetrical grid (Figure 4).

In Step 4, participants explained their reasoning for placing certain photos at the extreme ends of the spectrum, which represented strong similarity or dissimilarity to rural Piedmont. Finally, in Step 5, participants assessed their rural social identity using the scale by Krok-Schoen et al. (2015) and provided demographic information.

Data Analysis

The analysis started by importing Q sort data from rural and urban participants into Excel. The datasets were merged and uploaded to KenQ, an online data analysis tool chosen for enhanced data differentiation capabilities (Nazariadli et al., 2019a). The analysis included Pearson product-moment correlations and factor analysis, using principal component extraction and Varimax rotation to group Q sorts with similar image placements under the same factors.

This analysis aimed to reveal perspectives (factors) on perceptions of rural life in North Carolina’s Piedmont region and identify characteristics of individuals holding these perspectives (view-holders). Each Q sort represented a distinct participant, and those significantly loaded under the same factor had similar viewpoints, differing from those under other factors (Stephenson, 1935).

The analysis formed collective profiles for each identified perspective (factor), comprising composite Q sorts. In these composites, each Q item received a factor score, essentially a z-score, the normalized weighted average of scores from respondents exemplifying that factor (van Excel & de Graaf, 2005). These composites were then broken down to produce arrays of factor scores for all 40 items, each uniquely numbered (Table 1).

Note. ►* = Distinguishing photo at p < 0.01, z-Score is higher than in all of the other factors.*◄= Distinguishing photo at p < 0.01, z-Score is lower than in all of the other factors.21 and 31 are consensus statements with similar Z scores across factors.

Interpreting each composite Q sort, facilitating viewpoint definition, was supported by factor arrays, participant feedback on each photo, and a thorough analysis of image placement patterns within Q sorts (Stenner, 2009). Two types of image placements were particularly informative: distinguishing images, uniquely placed in one composite Q sort but not in others, highlighting what sets the viewpoint apart, and consensus images, appearing in similar positions across different Q sorts, indicating common ground among different viewpoints.

Findings

We streamlined our factor analysis by filtering out factors with Eigenvalues under 1 and keeping those with at least two significant loadings above ±.41 (±1.96 × standard error; with SE = 1/√(number of photos), p <.05) (Watts & Stenner, 2005). Using the scree plot, we determined the best number of factors and chose a four-factor solution for its clarity and interpretability. This solution encompassed 36 participants (16 urban/20 rural), explained 58% of the variance, and clearly differentiated four distinct perspectives.

Factor one balanced representation from both groups, with 7 rural and 5 urban participants. Factors 3 and 4 were predominantly rural (6 rural, 2 urban) and urban (2 rural, 9 urban) respectively. Factor 2 captured the perspectives of five rural individuals only. However, four urban participants' views did not align significantly with any factors, suggesting distinct opinions. Furthermore, the polarity of factors 3 and 4 was marked by participants with negative loadings, indicating completely opposite viewpoints (Stenner, 2009).

Factor 1: Pastoral and Quaint Rural Place

Note. RSI = Rural Social Identity index. Factor loadings indicate the extent to which a participant agrees or disagrees with factor. R = rural. U = urban.

Factor 1 encapsulated a perspective romanticizing rural life as pastoral and idyllic, with livestock grazing over wide open spaces. Adherents pointed to traits like quaintness, disarray, and a sense of being undeveloped as characteristic of the countryside. Shared by 12 individuals (four men, two each from rural and urban backgrounds, and eight women, five rural and three urban), this view accounted for 20% of the total variance. On average, participants showed a factor loading of 0.64, scoring an average of 11.33 on the Rural Social Identity index (RSI), indicating pronounced rural affiliation. Notably, this factor resonated more with younger adults.

The top five photographs (1, 7, 10, 5, and 3) related to this factor predominantly displayed randomness and herds of animals grazing freely in open lands. (Figure 6). They embodied Urbannormative themes such as unsystematic work (1, 10 & 3) and a connection with nature (5). Participant comments on specific images further emphasized this view. For example, on image 10 (4(F1), -2(F2), 0(F3), 1(F4)), R5 said, “Rural life usually includes livestock. These free-range pigs would not be allowed near a town.” Image 1 (4(F1), -1(F2), -2(F3), 0(F4)) prompted R3 to comment, “Ramshackle yard, too many animals for the size of the paddock, random assignment of the critters. That looks like a small homestead.” U20, reflecting on image 5 (3(F1), -1(F2), 1(F2), -1(F3)), remarked, “This is typical farmers day in the winter. Working through the winter is part of rural life.” Images ranked lowest (32, 20, 27, 19, and 35) presented views opposing Urbannormative ideals. On image 20 (-4(F1), -1(F2), -2(F3), 0(F4)), U19 commented, “This house does not look like a farm or rural house. It looks like a more urban or suburban design.”

Factor 1 advocates pictured rural life as unstructured, with free-roaming livestock across expansive landscapes. Their views align with two common public narratives about rural areas—pre-modernity and productivism. These narratives depict rural spaces as underdeveloped and engaged in traditional farming methods.

Factor 2: The Idealists: Small Scale and Healthy Food Production

Factor 2 captured the sentiments of five rural individuals with an idealized perspective, detached from present rural conditions in Piedmont, North Carolina, focusing on awareness and sustainability. This cohort, three women and two men, accounted for 12% of the variance, with an average Rural Social Identity (RSI) score of 12.4 and an average factor loading of 86.6. Notably, this group included five of the six Native American participants in the study (Table 3).

Note. RSI = Rural Social Identity Index. Factor loadings indicate the extent to which a participant agrees or disagrees with factor. R = rural. U = urban.

The highest-rated photos (2, 26, 24, 4, and 17) for this group highlighted agricultural themes, with three (2, 4, 17) pre-categorized as anti-Urbannormative (Figure 7). R10, commenting on distinguishing image 24 (1(F1), 4(F2), 1(F3), 2(F4)), said, “We must learn to recycle and compost everything for the good of the planet. No landfills and mountains of garbage floating in the ocean and blowing all over our planet.” Another comment on distinguishing image 2 (-1(F1), 4(F2), 0(F3), 0(F4)) came from R9, who said, “We need to eat more greens.”

The least favored images by Factor 2's proponents included photos (32 & 27) rejected by Factor 1's group. The other three images depicted themes of "disconnection from nature", "modern/forward-looking", and "systematic work", fitting the anti-Urbannormative narrative. These participants opposed modern, unsustainable agricultural methods seen as harmful to health. For instance, R11 critiqued distinguishing image 14 (1(F1), -4(F2), -2(F3), 2(F4)), “Now we have too many corporate farms that use unsafe farming practices and get subsidies, and this is wrong… Poisonous chemicals that are put on our food should be banned."

Factor 2 adopted the productivism viewpoint, sidestepping stereotypical notions about North Carolina's rural conditions. The researchers' extended engagement revealed a conscious avoidance of preconceived representations. They enacted a subtle disavowal of established discourse, foregrounding their nuanced understanding. As Foucault (1980) suggests, this informed stance is linked to power dynamics. By presenting their knowledge, participants navigated entrenched power relations in the narrative of rural life.

Factor 3: Peaceful Rural Idyll

Advocates of this viewpoint envision rural North Carolina as tranquil, appreciating a relaxed landscape beyond production and agriculture. They aim to correct misrepresentations that overshadow its true nature, countering unfavorable images on the Q sort grid's “Most Unlike” side (Short, 2006).

Mainly shared by older rural residents, this viewpoint contributed to 12% of the variance. Their average factor loading was 0.61, with a moderate rural self-association (RSI score: 11.37). Urban participant U3's views matched rural backers of this factor, while U12 held an opposing stance (Table 4).

Note. RSI = Rural Social Identity Index. Factor loadings indicate the extent to which a participant agrees or disagrees with factor. R = rural. U = urban.

The top images (37, 30, 28, 40 & 26) highlighted the serene and picturesque nature of rural life (Figure 8), albeit reflecting certain Urbannormative ideals like "idyllic" (37 & 28), "romantic" (30 & 40), and "connectedness with nature" (26).

Regarding image 37 (0(F1), 0(F2), 4(F3), 0(F4)), R3 commented, "Beautiful, peaceful looking sunset. Love this time of day and enjoying the beauty of nature on my farm." On image 30 (-2(F1), 0(F2), 4(F3), -4(F4)), R4 said, "Quiet country living… Celebrating agriculture, views and slowing down of life." Challenging negative clichés, they placed three images linked with "intimidating" anti-Urbannormative themes (32, 27, & 11) at the “Most Unlike” end. U3's take on image 11 (2(F1), 1(F2), -4(F3), -2(F4)) was "that is totally least like my expectations of rural life. I know it is a part of farming and raising livestock, but it is not what I like to see.” R5 on image 32 spoke of the adverse impact that misconceived views of dogs in rural settings can have on actual perceptions.

Factor 3 supporters resisted clichéd rural depictions, presenting an anti-idyll model contrasting rural brightness (wellbeing) with darkness (terror), emphasizing the "popular imagination" of "bucolic tranquility and communion with nature" (Bell, 2006).

Factor 4: The Realists: The Pastoral Rural North Carolina

This perspective links farming to rural North Carolina, emphasizing genuine depictions. Mainly urban (four women, five men, two rural women), they adopted an objective realist stance, seeking accurate representations of rural life. Despite more urban members, their social identity scores below 10 indicate a strong rural connection (8.18). Representing 14% of the variance, they averaged a factor loading of 59.6 (Table 5).

Note. RSI = Rural Social Identity Index. Factor loadings indicate the extent to which participant agrees or disagrees with factor. R = rural. U = urban.

The five highest-ranked images (17, 7, 28, 8 & 29) primarily depicted productive aspects of rural life (Figure 9). U6 commented on distinguishing image 29 (0(F1), -4(F2), -3(F3), 4(F4)), "North Carolina has one of the greatest pig populations in the States," and U2 added, "pig farms are very common in NC." The five lowest-ranked photos included distinguishing images 30 & 40, categorized under the "peaceful" Urbannormative theme. On distinguishing image 30 (-2(F1), 0(F2), 4(F3), -4(F4)), U6 said, "Looks like a scene out of a Nicholas Sparks book," and U17 observed, "This seems more like something you'd see in California. It looks more like an upscale vineyard than the typical farm one would come across." Regarding on distinguishing image 40 (-3(F1), -2(F2), 3(F3), -4(F4)), U18 remarked, "Not many places have log cabin-themed bathrooms in the area. It is a bit fictitious to assume such a thing in a country-oriented environment."

Factor 4 advocates sought objectivity, separating personal beliefs from analysis. Unlike Factor 2 (emphasizing harmful production) and Factor 3 (resisting stereotypes), they opted for a direct, literal interpretation without delving into broader themes. Their rural outlook mirrored a hegemonic, global pastoralist vision influenced by tourism and media portrayals (Bell, 2006).

Discussion

This study explored four mental models of rural representation among microentrepreneurs and urban visitors in North Carolina's Piedmont, shedding light on the influence of Orientalism and Urbannormativity in rural tourism (Short, 1991). The initial cohort depicted the Piedmont as a pastoral haven, aligned with Urbannormative discourses portraying rural life as disordered, basic, and a refuge from contemporary, technologically influenced existence.

Factor Two participants, mainly Native American, resisted artificial representations, engaging in Foucauldian resistance against postcolonial and Urbannormative influences (Wei, Qian & Sun, 2018). Their maintenance of self-reflective narratives revealed a profound understanding of oppressive narratives imposed on their socio-cultural and environmental realities.

Factor 3, primarily senior rural inhabitants, actively contested stereotypes and advocated for positive rural depictions. However, discrepancies between Factor 3 and Factor 4 emerged, indicating diverse interpretations influenced by media-fostered rural expectations (Cloke, 2006). Factor 4, mostly urban, might conceptualize rural spaces as economically subservient, challenging rural tourism efforts to attract urban visitors.

The study's implications underscore the need for strategic rebranding by rural advocates to overturn the functional perception of rural areas. Two distinct rural participant groups (Factors 2 and 3) counter Urbannormative biases, revealing an urban-rural divide in expectations. A one-size-fits-all approach may exacerbate this gap, highlighting the importance of initiatives fostering mutual understanding.

Capitalizing on shared understanding between rural hosts and urban visitors is crucial in tourism, emphasizing the need for authentic rural representations that preserve unique identities. Countering rural conformity to urban norms is imperative for preserving historical narratives, and emphasizing rural voices is vital for sustainable tourism, necessitating policies that support genuine representations for deeper visitor understanding (Wang & Law, 2017).

This study opens several avenues for future research. In the age of digital connectivity, social media and VR/AR have the potential to offer more comprehensive and authentic representations of rural areas. Utilizing these platforms can help challenge stereotypes and provide a richer portrayal of rural life (Saedi et al., 2021; Saedi & Rice, 2022). Integrated marketing strategies and technologies such as VR and AR that allows for differentiating between individual’s conscious perceptions of specific environmental characteristics and their subconscious reactions to the same environment (Saedi & Rice, 2020), can potentially bridge this gap, enhancing the appeal of rural communities and contributing to the sustainable development of rural tourism.

Conclusion

Navigating rural destination promotion for urban audiences is uncharted but vital. Grounded in Orientalism and Urbannormativity, our study delved into power structures shaping harmful stereotypes about marginalized communities, justifying exploitation. Engaging rural microentrepreneurs and urban visitors through Visual Q Methodology revealed four diverse mental models of rurality. Insights emphasize the nuanced interplay between urban and rural perspectives, guiding authentic and appealing destination marketing. Visual Q Methodology proves a potent tool for dissecting complex meanings, empowering stakeholders to craft honest narratives aligning representation with reality. This research emphasizes the need for tourism promotion to respect rural authenticity, ensuring narratives resonate truthfully and compellingly.

Footnotes

1 Urbannormative concepts in this row

2 Anti-Urbannormative concepts in this row

References

- Ashcroft, B., Griffiths, G., & Tiffin, H. (2002). Post-Colonial Studies: The Key Concepts. Routledge.

- Bandyopadhyay, R., & Morais, D. B. (2005). Representative dissonance: India’s self and western image. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(4), 1006-1021.

- Bell, D. (2006). Variations on the rural idyll. In P. ClokeT. Marsden & P. Mooney, The handbook of rural studies (pp. 149-160). London: SAGE Publications.

- Brown, S. R. (1980). Political subjectivity: Applications of Q methodology in political science. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Brown, S. R. (2005). Applying Q methodology to empowerment. In D. Narayan (Ed.), Measuring empowerment: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives (pp. 197-215). Washington: The World Bank.

- Chambers, D., & Buzinde, C. (2015). Tourism and decolonisation: Locating research and self. Annals of Tourism Research, 51, 1-16.

- Cloke, P. (2006). Conceptualizing rurality. In P. Cloke, T. Marsden & P. Mooney (Eds.), The handbook of rural studies (pp. 18-28). London: SAGE Publications.

- Dangi, T. B., & Jamal, T. (2016). An integrated approach to “sustainable community-based tourism”. Sustainability, 8(5), 475.

- Dodds, R., & Butler, R. (Eds.). (2019). Overtourism: Issues, realities and solutions (Vol. 1). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

- Echtner, C. M., & Prasad, P. (2003). The context of third world tourism marketing. Annals of Tourism research, 30(3), 660-682.

- Feighery, W. G. (2012). Tourism and self-Orientalism in Oman: a critical discourse analysis. Critical Discourse Studies, 9(3), 269-284.

- Ferreira, B. S., Morais, D. B., & Lorscheider, M. (2015). Using web marketplaces to reach untapped markets. North Carolina Cooperative Extension Services.

- Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge; selected interviews and other writings, 1972–77. Brighton: Harvester Press.

- Fulkerson, G. M., & Thomas, A. R. (2013). Urbanization, Urbannormativity, and Place-Structuration. In M. Fulkerson & A. R. Thomas (Eds.), Studies in Urbanormativity: Rural Community in Urban Society (pp 5-30). Lanham: Lexington Books

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2015). Tourism and Water. Channel View Publications.

- Halfacree, K. H. (2017). Locality and social representation: space, discourse and alternative definitions of the rural. In The rural (pp. 245-260). Routledge.

- Hall, M.C., & Tucker, H. (Eds.). (2004). Tourism and Postcolonialism: Contested Discourses, Identities and Representations (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Jafari, J., & Scott, N. (2014). Muslim world and its tourisms. Annals of Tourism Research, 44, 1-19.

- Jansson, D. R. (2005). ‘A geography of racism’: internal orientalism and the construction of American national identity in the film Mississippi Burning. National Identities, 7(3), 265-285.

- Jenkins, O. (2003). Photography and travel brochures: The circle of representation. Tourism Geographies, 5(3), 305-328.

- Jørgensen, M. W., & Phillips, L. J. (2002). Discourse analysis as theory and method. London: SAGE Publications.

- Krok-Schoen, J. L., Palmer-Wackerly, A. L., Dailey, P. M., & Krieger, J. L. (2015). The Conceptualization of Self-Identity among Residents of Appalachia Ohio. Journal of Appalachian Studies, 21(2), 229-246.

- Lähdesmäki, M., Siltaoja, M., & Spence, L. J. (2019). Stakeholder salience for small businesses: A social proximity perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 158, 373-385.

- Lugosi, P., Robinson, R. N. S., Walters, G., & Donaghy, S. (2020). Managing experience co-creation practices: Direct and indirect inducement in pop-up food tourism events. Tourism Management Perspectives, 35, 100702.

- Maoz, D. (2006). The mutual gaze. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(1), 221-239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.10.010

- McKeown, B. & Thomas, D. B. (2013). Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences: Q methodology. CA: SAGE Publications.

- Mokry, S., & Dufek, O. (2014). Q method and its use for segmentation in tourism. Procedia Economics and Finance, 12, 445-452.

- Morgan, N., & Pritchard, A. (1998). Tourism promotion and power: Creating images, creating identities. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Morgan, N., & Pritchard, A. (2019). Gender matters in hospitality (invited paper for ‘luminaries’ special issue of International Journal of Hospitality Management). International Journal of Hospitality Management, 76, 38-44.

- Munar A. M., Jacobsen J. K. S. (2014). Motivations for sharing tourism experiences through social media. Tour. Manag. 43, 46–54.

- Nazariadli S. (2017c). VQMethod [Online research tool]. Available at: https://vqmethod.com; http://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/D3WH6

- Nazariadli, S., Morais, D. B., Barbieri, C., & Smith, J. W. (2017a). Does perception of authenticity attract visitors to agricultural settings? Tourism Recreation Research, 43(1), 91-104.

- Nazariadli, S., Morais, D. B., Supak, S., Baran, P. K., & Bunds, K. S. (2019b). Assessing the visual Q method online research tool: A usability, reliability, and methods agreement analysis. Methodological Innovations, 12(1), 2059799119832194

- Nazariadli, S., Morais, D.B., Bunds, K., Supak, S., & Perver, B. (2019a). Tourism Microentrepreneurs’ Self-representation through Photography: A Counter-hegemonic Approach. Rural Society.

- Paige, J. B., & Morin, K. H. (2016). Q-sample construction: A critical step for a Q-methodological study. Western journal of nursing research, 38(1), 96-110.

- Ramlo, S. (2015). Theoretical Significance in Q methodology: A Qualitative Approach to a Mixed Method. Research in the Schools, 22(1).

- Roggenkamp, K. (2008). Seeing Inside the Mountains: Cynthia Rylant's Appalachian Literature and the" Hillbilly" Stereotype. The Lion and the Unicorn, 32(2), 192-215.

- Saedi, H., & Rice, A. (2020). Minor Change for Major Impact: How Can Minor Changes in the Daily Urban Environment Impact an Aspect of Psycho-Physiological Health? Prometheus, 4, 98-101.

- Saedi, H., & Rice, A. (2022). A Deeper Understanding of the Impact on the Restorative Quality of Green Environments as Related to the Location and Duration of Visual Interaction. Journal of Digital Landscape Architecture, 412-424. https://doi.org/doi:10.14627/537724040

- Saedi, H., Einifar, A. R., & Barati, N. (2021). The Impact of Micro Interaction with Natural Green Elements Through Virtual Reality on Attention Restoration (In a High-Rise Residential Building's Lobby). Journal of Architecture and Urban Planning, 13(30), 5-21. https://doi.org/doi:10.30480/aup.2021.2341.1442

- Said, E. (1978). Orientalism: Western representations of the Orient. New York: Pantheon.

- Salazar NB (2012) Tourism Imaginaries: A Conceptual Approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 4, 39(2):863-882.

- Schein, L. (1997). Gender and internal orientalism in China. Modern China, 23(1), 69-98.

- Seale, E. (2013). Coping Strategies of Urban and Rural Welfare Organisations and the Regulation of the Poor. New Political Economy, 18(2), 141-170.

- Short, B. (2006). Idyllic ruralities. In P. Cloke, T. Marsden, & P.H. Mooney (Eds.), Handbook of rural studies (pp. 133–148). London: Sage Publications.

- Short, J. R. (1991). Imagined country: Society, culture and environment. London: Routledge.

- Stainton Rogers, R. (1995). Q methodology. In J. A. Smith, R. Harre, & L. Van Langenhove (Eds.), Rethinking Methods in Psychology (pp. 178-192). CA: SAGE Publications.

- Stenner, P. (2009). Q methodology as a constructivist methodology. Operant subjectivity: the international journal of Q methodology, 32(1-3), 46-69.

- Stephenson, W. (1935). Technique of factor analysis. Nature, 136(3434), 297.

- Torres, R., & Momsen, J. (2011). Tourism and agriculture: new geographies of consumption, production and rural restructuring. Routledge.

- Tussyadiah, I., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2009). Mediating Tourist Experiences: Access to Places via Shared Videos. Annals of Tourism Research, 36, 24-40.

- Van Exel, N.J.A., & de Graaf, G. (2005). Q-methodology: A sneak preview.

- Wang, L., & Law, R. (2017). Identity reconstruction and post-colonialism. Annals of Tourism Research, 63, 203-204.

- Wang, Y. A., & Morais, D. B. (2014). Self-representations of the matriarchal Other. Annals of Tourism Research, 44, 74-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.09.002

- Watts, S., & Stenner, P. (2005). Doing Q methodology: theory, method and interpretation. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2(1), 67-91.

- Wei, L., Qian, J., & Sun, J. (2018). Self-orientalism, joke-work and host-tourist relation. Annals of Tourism Research, 68, 89-99.

- Wijngaarden, V. (2016). Tourists’ agency versus the circle of representation. Annals of Tourism Research, 60, 139-153.

- Woods, M. (2017). Deconstructing rural protest: the emergence of a new social movement. In The Rural (pp. 411-428). Routledge

- Yan, G., & Santos, C. A. (2009). “CHINA, FOREVER”: Tourism discourse and self-orientalism. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(2), 295-315. Zhang, C. X., Decosta, P. L. E., & McKercher, B. (2015). Politics and tourism promotion: Hong Kong’s myth making. Annals of Tourism Research, 54, 156-171.

Open Peer Review